Andrew Jackson

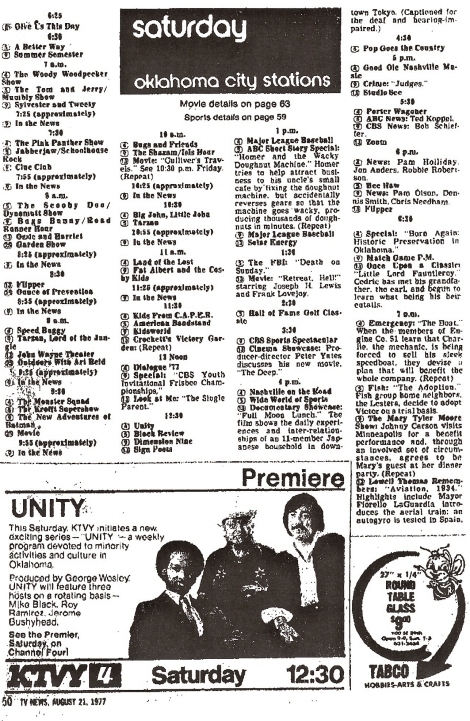

excerpt from: http://www.presidentprofiles.com/Washington-Johnson/index.html

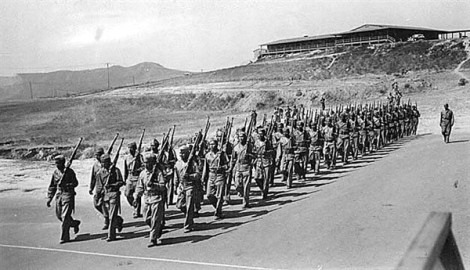

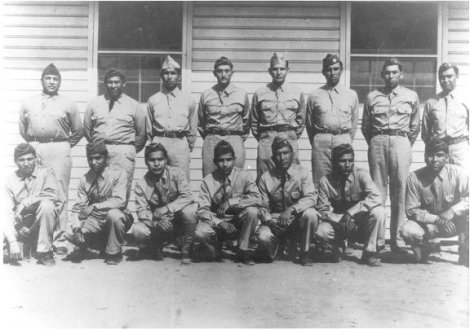

……Efforts to make removal treaties with the Indians began as soon as Jackson took office and continued throughout his presidency. Jackson himself occasionally participated in the negotiations. The administration focused on the southern tribes, beginning in September 1830 with the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek with the Choctaw, and proceeding with the Creek, Chickasaw, and, in 1835, the Cherokee. Less well known are the treaties made with the generally weaker tribes of the Old Northwest, such as the Chippewa, Ottawa, and Potawatomi. Over the period of Jackson’s presidency, the United States ratified some seventy treaties, affecting approximately forty-six thousand Indians…..

http://www.prairienet.org/prairienations/ok.htm

Jim Fay, Ph.D.

9/13/07

Abstract: The etymology of “‘OK” based on the Choctaw “okeh” that was cited in dictionaries well into the twentieth century, and how that etymology came to be replaced by one formulated by Allen Read. Also notes and information about this document .

INTRODUCTION

Consider the expression “O.K” as it was used in the early to mid 1960’s.

Peter, Paul and Mary were singing, in the song “All Mixed Up”:

You know this language that we speak,

is part German, Latin and part Greek

Celtic and Arabic all in a heap,

well amended by the people in the street.

Choctaw gave us the word “okay”…

The song was written by Pete Seeger, who was at the center of the folk music scene as the composer of such songs as “This Land Is Your Land.” Seeger said he based his statement about “okay” on Choctaw traditions such as the one that Andrew Jackson heard the expression from the Choctaw during the Indian Wars before he passed it on to the rest of the world. (PETE) One apocryphal story has a Choctaw warrior using the expression to Andrew Jackson to express victory at the Battle of New Orleans in 1815. In 1840 a “Jackson Breast Pin” was advertised celebrating “the hero of New Orleans and having upon it…the very frightful letters O.K.”Also at the center of this folk music scene was the Okeh record label, “okeh” being recognized as the older spelling for “an Indian word.” The first Okeh records had a Native American silhouette logo on the label.

The expression was still occasionally spelled “okeh” in popular usage at that time in America, and that was a preferred spelling in other parts of the world such as Germany and Russia. It is still a preferred spelling in those parts of the world.

Dictionary entries of the day routinely cited a Choctaw etymology based on resources going back to 1825, especially an 1870 Choctaw Grammar which treated the expression in some detail, saying the expression meant “it is so and in no other way” and was often used as an interjection to get the attention of the user. When spoken more quietly it expressed “thank you.”

The US Postal Service was introducing new changes including two-letter abbreviations for the states. Oklahoma was given the abbreviation ‘OK,’ which fit in very well with the myriad of Choctaw and other Muskogeon place names. For example, the village that had been “North Muskogee” until that name was changed to “Okay” in 1919 became officially designated as “Okay, OK”

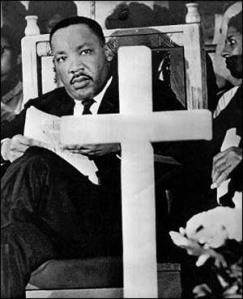

Although the Choctaw etymology was widely accepted during the early 1960’s, other events were also happening at that time in the etymology of “OK.” Columbia professor and editor of the scholarly American Speech, Allen Walker Read, had been promoting for 20 years the importance his discovery of a couple of early uses of “OK” dealing with Martin Van Buren. He argued that the popular usage of “OK” was derived from an acronym for “Old Kinderhook,” which referred to Van Buren’s birthplace.

There were literally dozens of instances of “OK” in the published record before and after the instances discovered by Read. The 1830’s and 40’s was the time of an extremely popular fad in which normal expressions were given facetious or “sportive” spellings and acronyms such as “N.C.” for “’nuff ced” or “K.Y.” for “know yuse.” “OK” was the basis for an endless array of these facetious acronyms, and many linguists saw no reason why “Old Kinderhook” was any more important in the life of the expression than any of those other uses such as “Orful Katastrophe,” “Out of Kash” or — by far and away the most popular — “Oll Korrect,” which was often associated with Jackson.

Nevertheless, Read was very zealous in promoting the “Old Kinderhook” etymology, so zealous that the Dictionary of American English (DAE) editor in charge of the OK entry published a paper in American Speech pointing out that the “Old Kinderhook” was not the origin of the expression and arguing it was not even a very significant component of the etymology. He argued that the ‘Old Kinderhook’ etymology be abandoned.

That paper led Read to publish a series of six papers in the 1963 and 1964 issues of American Speech. The papers offered an encyclopedic account of the various uses of the “O.K.” expression by whatever spelling. But, more importantly, the papers also served notice about how Read was more than willing to use the pages of American Speech to treat anyone who did not wholeheartedly endorse his ‘Old Kinderhook’ etymology.

Four of those papers will be discussed here.

But before looking at those papers, we will take a look at a significant body of American literature that pre-dates by almost a decade and a half the uses of “O.K.” beginning in 1839 and cited by Read.

One final introductory note…in this discussion the expression will be rendered by whatever spelling was used by the original writer. In those instances when the expression is used in general, it will be spelled “OK” that implies no particular historical pedigree.

EARLY CHOCTAW LITERATURE

The expression pronounced “okay” and denoting affirmation — “it is so and not otherwise” — appears in Choctaw literature more than a decade before the acronym or pseudo-acronym “O.K.” appears in English literature. Linguists refer to it as a particle in that it does not modify any particular noun, verb or other modifier of the sentence in which it appears. It merely affirms or emphasizes the point being made.

The authorship of this early Choctaw literature is universally ascribed to two Presbyterian missionaries to the Choctaw, Cyrus Byington and Alfred Wright. Although those names seldom if ever appear as authors on the title pages of the publications, they are almost invariably given in brackets as the authors in citations of those works. Wright was a full-blood Choctaw, and he and Byington sought to develop material to evangelize and educate the Choctaws on one hand and to train missionaries and teachers on the other.

These two men produced either independently or in collaboration a body of literature that included an 1825 reading and spelling book with translations apparently aimed primarily for non-Choctaws; an 1829 Chahta vba isht taloa holisso or, Choctaw hymn book; an 1831 translation of passages from the Book of Genesis, History of Joseph and his Brethren; an 1835 Triumphant deaths of pious children; an 1836 Chahta i kana or The Choctaw friend; an 1839 volume The Acts of the Apostles translated into the Choctaw language: Chisus Kilais, with the Choctaw subtitle “Im anumpeshi u’hliha u’mmona ku’t nana akaniohmi tok puta isht annoa, chaval anumpa isht atashoa hoke.”

These titles were followed by a host of similar works, many of them Bible translations, and all devoted specifically to evangelism and education. It might be noted that the titles of these early works is sometimes no more clear cut than the authorship of them. The title cited in a catalog might not be the title given on the title page at all, but rather a translation of the title or even merely a general description of the work.

The 1825 Choctaw spelling book consists of lists of spelling words and verb conjugations with English translations followed by translations of Bible passages. The particle”oke” or “hoke” is not included in these lists, but it is routinely used in the Bible verses translated at the end of that early book. After offering translations of The Lord’s Prayer and The Ten Commandments, the book offers a translation of The Parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus beginning with Luke 16:19, and it ends that verse with an expression ending in “-oke” to affirm or emphasize the point being made. That passage is about the rich man who lived in luxury every day, and the translation ends the first verse with something akin to “…the rich man lived in luxury every day, yes he did.” The “-oke” notation is used to end about half of the remaining verses translated in that early book, often with the “tok” particle to emphasize “in the past.”

The Choctaw use of the affirmative particle is virtually identical to one of the very common ways the expression “OK” is used in English. Take, for example, that quintessential use of “OK” in the sentence, “We arrived OK.” Perhaps that “OK” may not modify either “we” or “arrived.” In other words, it does not necessarily reflect on either the condition we were in when we arrived or how satisfactory our arriving was, but merely emphasizes the point that we arrived. This is especially the case in some situation in which our arrival is called into question. And so, for example, the comment “Someone said you never arrived” might well be met with “Oh, we arrived OK.” Indeed, we would probably see no contradiction at all in the declaration “Oh, we arrived OK, but we were too late” or “Oh, we arrived OK, but we were all sunburned, and Jack had a sprained ankle.”

The expression “OK” is not used is used to modify either “we” or “arrived.” It is rather used to affirm and emphasize the point being made. The statement says, in effect, “We arrived, we did” or “We arrived; it is so and not otherwise.”

At any rate, subsequent Choctaw spelling books and readers de-emphasized the spellings lists in favor of straight prose, and they made use of the particle. but they too never included it in the word lists or discussed it directly. The presumption was that the use of particle “oke” or “hoke” was so common and self-evident as to preclude any need for explanation or discussion for either its Choctaw or non-Choctaw readership.

The first spelling book in 1825 made rather fine distinctions regarding pronunciation, offering for example three separate ways of pronouncing the vowel “e” as a short “e,” as a long “a,” and as the “eh” sound. Later works adopted the much simpler pronunciations. The pronunciation guide (on page three of most editions of the speller) states simply that “o” is to be pronounced as the “o” in “note,” and “e” is to be pronounced as the “a” in “made.” It must be remembered that Byington and Wright had little or no interest in “expanding the envelope” of linguistic studies. They were concerned only with the most expeditious means of teaching and converting Choctaws and training teachers and missionaries, and the simpler orthographies fulfilled that requirement very admirably.

In the 1825 book most of the vowels had some diacritical mark attached to them. In subsequent works, such complications are almost, if not entirely, absent. A fluent speaker of Choctaw may observe some subtle nuances between the sound of “eh” and a short e, for example, but such subtleties were not essential for the purposes of the missionaries.

Using this straightforward and unambiguous orthography, the verb “oke” or “hoke” is pronounced “okay,” or “hokay.” Moreover, since expression comes at the end of sentence or is used as an interjection in the Choctaw language, the expression is easy for even a non-speaker of Choctaw to spot on paper, to hear in spoken Choctaw and to learn to use after some fashion or other.

The spelling book went through three editions before 1840 and eight editions before the end of the century. Editions after the first edition were usually referred to as Chahta holisso Ai isht ia vmmona or in English as A Spelling book written in the Chahta language or simply as Chahta holisso, that is, “The Choctaw Book.”

After the death of Wright in 1853 and Byington in 1868, others published the material those individuals had developed but not published because it was not directly concerned with evangelism or education. This situation gave rise to the curious phenomenon in which those missionaries were listed as authors of new works from more than a century beyond the grave. They are the authors, for example, of Nitak moma ilhpak pin or Our Daily Bread published by the American Bible Society in 1978.

The Dictionary is a good example of the timeless nature of the material. In 1915 the highly respected Bureau of American Ethnology of the Smithsonian published A dictionary of the Choctaw language with Byington as the principle author. That Dictionary has been repackaged and reprinted countless times since, for example by Oklahoma City Council of Choctaws, Inc., in 1972; by the Scholarly Press in 1976; by the Central Choctaw Council, in 1978; by the Title VII ESEA funded Bilingual Education Program located in McCurtain County, Idabel, Oklahoma in 1985; by Native American Book Publishers, in 1990; by the Global Bible Society in 1995; and by others. It was microfilmed by the Microfilming Corporation of America in 1974 and by the Law Library Microform Consortium in 1990.

The earlier works published by Byington and Wright themselves also continued to be republished to this day, but, because of their more limited application, not to the extent of works such as the Dictionary. The 1829 hymn book, for example, was reprinted by the John Knox Press in 1964; by the Home Mission Board of the Southern Baptist Convention in 1988; and by the Native American Bible Academy in 1997.

The publication of Byington’s Choctaw Grammar is a particularly interesting story. The widely respected linguist and ethnologist Daniel Brinton published a fuller version of the kind of material that had gone into the very first 1825 spelling book but then abandoned to streamline the evangelism and education efforts. Byington had finished the first draft of a Choctaw grammar in 1834, and was asked to submit the work to the Smithsonian in 1852, which he did It was well received, but the final revision seems to have been lost. Brinton published it in 1879, and made a presentation on it to the American Philosophical Society in February of the same year. The Grammar was subsequently published by the Bureau of American Ethnology in 1915 and on other occasions.

The second reason the Grammar is of interest is that it first treats at some length an important aspect of the nature of Choctaw conversation and oratory that was only infrequent and incidental in the formal literary exposition of the previous publications, and that is the heavy and effective use of interjection. Both the historical record and contemporary evidence demonstrates that Choctaw speakers delight in rhetorical flourishes such as interjections and rhetorical questions to invite a response from the listener. ( Badger, 6-7 )

It should be remembered that the works published by Wright and Byington were almost exclusively spelling and grammar books and translations of the Bible, not conversation. Moreover, the literary style adopted by the missionaries in biblical translation was quite different from vernacular, conversational Mississippi Choctaw. ( Badger, 16, note ) Consequently, these early books do not necessarily offer good examples of vernacular, conversational Choctaw. One of the early Choctaw works that was an exception to this was the 1835 book Triumphant Deaths of Pious Children, which contains a good bit of conversation, and these passages of dialogue include interjections and rhetorical questions to involve the listener in the dialogue.

The Grammar took some pains to treat these various rhetorical devices in more detail than previous works had done. The syntax of most interest to English users of “okay” is the “affirmative contradistinctive” and the “objective interjection.” As noted earlier, that syntax meant almost exactly what “okay” means today, “it is so and not otherwise.” ( Byington, 14-15, 55 )

Byington distinguished between “okeh” and “okah”:

|

ok takes ah in okah, a distinctive and definite predicate…

ok takes eh in okeh, a distinctive and absolute predicate… (15) |

Okeh was also used as the objective interjection:

|

These are used to excite the attention of the party addressed… (55)

|

This is also virtually identical to the way the expression is used in English. How many meetings or classes have begun with “OK, let’s get started…”? One textbook on public speaking offers the admonition not to begin the speech with “OK…”

Moreover, “OK” is routinely used in English as a particle to affirm or emphasize the point being made, often in a rhetorical question. For example:

“Can we get started?”

“OK.”

In this case the “OK” is not so much a yes/no answer as it is an affirmation of the point being made in the rhetorical question.

Linguists and ethnologists have noted the similarity in the use of the expression in Choctaw and English, but since Read published his series of papers, this point is given the most hesitant treatment. One treats it in an “amusing” footnote:

|

While the existence of this Choctaw word is known to etymologists (see Thomas Pyles, Words and Ways of American English /New York: Random House, Inc., 1952/, pp. 159-60) there are two points which are not generally taken into consideration. One is that the lingua franca built on Choctaw could have easily contained this word and spread its usage over a wide area. The other is the prevalence of okeh in Choctaw speech. It was amusing to note the occurrence of okeh in Choctaw conversations in much the same syntactic and semantic environments as the American OK occurs. If OK came out of the American back woods as suggested by Pyles, then Choctaw would be a sensible source. ( Badger, 16, note ).

|

The book by Thomas Pyles mentioned in this note discusses Native languages in particular for some eight pages and is elsewhere sprinkled with references to Native and frontier contributions to American vernacular speech. Chapter Seven, “Later American Speech: Coinages and Adaptations,” which discussed the expression “okeh” begins with these words:

|

The War of 1812 and the appearance on the American scene of the frontiersman — both in the flesh and as a national symbol — mark the beginning of an indigenous psyche Americana which is striking reflected in the flood of Americanisms originating in the nineteenth century. (154)

|

The book accepted the “Old Kinderhook” etymology but also included a small but straightforward mention of the Choctaw etymology of “OK.” Moreover, Pyles said that Read built up a convincing case for “Old Kinderhook” but admitted the possibility and discussed the implications of it just being “a newspaper writer’s fabrication of an etymology after the fact.” (162)

It might be noted, however, that in a 1982 work published after Read’s series of papers Pyles showed no such ambivalence. He not only ridiculed evidence of pre-Kinderhook or non-Anglo-Saxon uses of the expression, including his own 1952 work, but disparaged that evidence as the romantic product of “the ingenuity of amateur etymologists.” (274) While the 1952 work treated Indian languages (in eight pages) as a significant source of loan words into American English, in 1982 he peremptorily dismissed Indian languages in a single paragraph within a five-paragraph section on “Slavic, Hungarian, Turkish, and American Indian” which he says are “[v]ery minor sources of the English vocabulary.” (309) On the second to the last page of the 1982 book, Pyles reiterated that Indian languages do not have significant usage in American English and what usage there is occurs mainly in literature, such as in the works of James Fenimore Cooper. (310)

The central place of Choctaw as the lingua franca of the frontiersman as suggested in Pyles’ 1952 book is supported by a World Cat survey of the publications during this time by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, which produced the Byington and Wright books. Such a survey indicates that the Native cultures that received the most attention were the Choctaw and related Muskogean people. Cherokees received the second most attention.

Moreover, Choctaw phrases using some form or spelling of “okeh” were precisely those phrases that would be familiar even to people with no particular interest in the language culture. One such phrase, “Yak oke,” was and is a good example. “Yak oke,” by various spellings, means “Thank you,” but may also be used to express joy when spoken quickly or regret when spoken slowly. (Byington, Grammar, 369) Moreover, about the first two expressions one learns about any language are those for “yes” and “thank you.” Just as people today who profess no knowledge of or interest in Spanish still know the words “sí” and “gracias,” or people who profess no knowledge of or interest in French know the meaning of “oui” and “merci,” so it was that people of the 1800’s who were interested in the frontier undoubtedly knew of “oke” and “Yak oke.” The fact that they seldom, if ever, wrote the expressions or used it in formal discourse does not mean they did not use them.Choctaw expressions based on some form of “oke” are precisely those expressions learned by those people with even the most fleeting contact with the language and culture. Even today, in web pages that do not by any means deal with the Choctaw language, if those pages do include a phrase or two of Choctaw, those phrases will almost invariably be based on some form of “oke.” The phrase “yakoke” or “yak oke” used in its “Thank you” sense is a popular feature of these pages. Some rendering of “oke” is often used to proclaim “I am Chahta (Choctaw).” or “We are Chahta.”

In short, anyone with even a passing interest in Choctaw culture has occasion to be familiar with “oke.” That may account for why the word was used constantly in the very early Choctaw spelling and reading books, but never treated formally in the word or expression lists or conjugations.

Modern reader may not appreciate the how widespread the use of the “okeh” spelling once was in vernacular American speech, a use documented in the mention of “okeh” someplace in entries for “O.K.” or “okay” in modern dictionaries, often with the notation the spelling is obsolete.

Woodrow Wilson, who was a highly respected historian and author of, among other works, the five volume A History of the American People before he became President, was something of a campaigner for “okeh,” and always used that Choctaw spelling to emphasize its Native origins. He did not use the spelling “O.K.,” he said “Because it is wrong.” – Wilson, 145

The Arrow shirt company marketed an Okeh collar for a while with the slogan “all that its name implies.” The advertisers felt no need to explain to the public what it was the name implied. (The author is indebted to Elina Smith of Cluett, Peabody & Co., Inc., New York, who included photocopies of three “Okeh” shirt collar ads in an April 29, 2002 letter.)

“Okeh” continues to be the favored spelling for the expression in some other languages, notably German and Russian. It may not be included in their dictionaries, but the “okeh” is alive and well in vernacular usage, as demonstrated by web searches of those languages. A Russian language search for “okeh” done by a competent Russian language researcher on a computer configured to the Cyrillic alphabet yields primarily, as any web search for “okeh” does, a mass of information about records by “Okeh” artists. But included in those listings is Russian vernacular use of “okeh,” most notably as the names of the businesses that have flowered in the new-found freedom of recent years, names that indicate the New World aspirations on which those businesses are based in import/export, computers, market research, consulting and so forth.

Before leaving the discussion of the substantial body of material by Byington and Wright, perhaps a couple of points are in order. First, this body of work has been taken very seriously for some 175 years and is taken seriously today by a variety of scholarly and religious institutions. A review of the three editions of the spelling book published before 1840 or the array of the institutions reprinting the Dictionary, for example, should dispel any notion that this material can be dismissed as silly or trivial buffoonery or as some kind of Tonto-esque “pop culture” gag.

The second point is an ironic counterpoint to the first. Nothing in this body of material should be taken as an effort on the part of Byington, Wright or Brinton to engender an appreciation for the Choctaw language or culture. Quite the contrary, the work of those individuals was devoted to, as Brinton put it in his introduction to Byington’s Grammar, “redeeming the [Choctaw] nation from drunkenness, ignorance and immorality to sobriety, godliness, and civilization.” (4) The whole body of evidence is predicated on the assumed superiority of civilized culture over uncivilized culture and on efforts to eradicate one culture in favor of the other.

Byington, Wright and Brinton would be appalled at the notion that their work might, some 150 years later, lead to some increased appreciation of traditional, uncivilized Choctaw culture, or that the work might play any part in expressions from the language of “ignorance and immorality” finding their way into the language of “godliness and civilization.”

READ’S “FOLKLORE” PAPER

One of Read’s papers was entitled “The Folklore of ‘O.K.'” but was a review of what most historians and the general public would be more apt to call history than folklore. In that paper he says that “[o]f all the folklorist stories about the origin of O.K., the cleverest and most seductive” is that it is derived from the Choctaw okeh. (14)

This etymology was the one given by dictionaries well into the twentieth century. Read cites in part a couple of these dictionaries. One was the New Century Dictionary:

|

A humorous or ignorant spelling of what should be *okeh <Choctaw (Chakta) okeh. . .: a use that may be compared with that of the Hebrew and European amen .’ – Emery, V. I, 1179; “Folklore,” 17, note

|

Another was Webster: “Prob. fr. Choctaw okeh it is so and not otherwise,” which was retained until 1961. (17, note)

However, Read excludes from his quote a rather crucial aspect of this Choctaw usage documented by Byington and included in the New Century dictionary entry, and that is the “interjectional” nature of the expression when “used to excite the attention of the party addressed.”Another nineteenth century Choctaw grammar, Allen Wright’s Chakta Leksikon, spelled the expression “okah,” “hokah,” or “yokah” and translated it as “it is, usually used in reply to a question with emphasis” – “Folklore,” 15

Read did not mention that Funk and Wagnals included the term “okeh” as a separate entry from “OK” in their 1941 edition and quoted the Byington grammar. Moreover, although some of the works by Byington or Wright had been reprinted repeatedly by respected scholarly, cultural and religious institutions for over a century, Read did not treat any of them in the text but merely mentioned them as a digression in a footnote about another work.

Read surveys several of the “backwoods” associations with the expression.

John Jacob Astor became the nation’s first millionaire by trading with the Indians for furs. In large part this trading was done throughout the section of the country in which Choctaw, or some derivative of it, was the lingua franca noted in the quotation above. One dictionary of colloquialism says that Astor used “OK” to approve of business transactions with other traders. Read says that it is “altogether probable ” that Astor used “OK” from 1839 until his death in 1848. (“Folklore,” 13) Read’s pinpointing the date as 1839 most assuredly is based on his own assumptions about the etymology of the expression. The chronology of history presents an alternate view. If the evidence offered by Read is correct and Astor used “OK” in reference to other traders, it must surely have been before 1834, when he retired from his activities in dealing with those traders. – Haeger , 243

Read reviews the first of the numerous accounts he discusses in his papers associating Andrew Jackson with “OK,” accounts that were set down on paper some time after the incident described. William H. Murray, whom Read repeatedly refers to as “Alfalfa Bill” instead of by his given name, was a student of Choctaw history, president of the Constitutional Convention instrumental in creating the state of Oklahoma and subsequently governor of that state. Murray offers an account of the Choctaw warrior Pushmataha using the phrase “si Hoka” very much in the unique way that “Okay!” is used today, and Jackson becoming enthralled with the emphatic expression. – “Folklore,” 15-16

In later papers Read presents several pieces of evidence (which he discounts out of hand) associating Jackson and William Henry Harrison both of whom launched their careers on the frontier with the expression “OK.”

Another piece of evidence Read dismisses out of hand is the work of W.S. Wyman, who he calls a highly praised “excellent scholar” and accomplished user of Choctaw.

Wyman offers a very earnest presentation of the evidence that Jackson learned “okeh” or “Hoka” from the Choctaw. He begins with “There is a tradition among the intelligent Choctaws of the old stock who once lived in Mississippi,” and ends with a ben trovata comment to the affect that, although the tradition is very enlightening and very consistent with history, the reader is not obligated to accept that tradition. Read interprets this modest phraseology to mean that Wyman fabricated these accounts. (“Folklore,” 15) When a scholar is accused of fabricating fraudulent historical evidence one would usually expect the accusation to be supported by some historical evidence that warrants the accusation. Read offers none, other than his suspicion, but treats his suspicions as established fact.

Admittedly, much of this evidence has all the earmarks of apocryphal anecdote. For example, until some historical documentation comes to light to support it, any scenario in which “okay” first passed into American English when Pushmataha used it to Andrew Jackson to indicate victory at the Battle of New Orleans is a little too pat and a little too neat not to arouse some skepticism. As a matter of fact, a look at the logistical setting of the story suggests that it probably would not have been Pushmataha who said to Jackson that the battle was going “okay.” ( Ward )

Nevertheless, reservations about individual anecdotes should not cause the entire body of evidence to be dismissed as “anecdotal” other than in the sense that all history is anecdotal. The point is that the well documented and widespread tendency to associate “OK” with the frontier is not based on the details of one particular anecdote. Quite the contrary, the apocryphal, almost mythical quality of these anecdotes in itself speaks volumes about how deeply rooted the term was in the frontier and in Native American (and native American) culture. The wide popularity of the expression had little to do with the specific details of any anecdote.

The central importance of Choctaw language as the lingua franca of the frontier at the time when the frontier was playing a large part in the molding of psyche Americana has already been noted. Moreover, as also earlier noted, the Choctaw expressions based on some form or spelling of “okeh” are precisely those expressions well known to people with even the most fleeting contact with or interest in the language or culture of the frontier.

Any discussion of whether Jackson could possibly know of these Choctaw expressions misses the point entirely. If anything, the question should be whether it is at all possible that Jackson could not have known of these expressions mentioned in the various anecdotes, and the answer to that is “no.” It is virtually inconceivable that Jackson could deal with Choctaws for years, adopt a Choctaw boy and yet remain unaware of these expressions, any more than one could deal with Mexicans for years and remain unaware of the expressions “sí” or “Gracias.”

Read’s treatment of the Choctaw “okeh” is a good example of the rhetorical technique known as “inoculation” in which evidence or arguments are acknowledged merely in order to give them a derisive dismissal. The attempt is to “inoculate” the audience against this evidence by creating an unwarranted antipathy to it that is difficult to overcome with reasoned argument. Indeed, the whole point of inoculation is to forestall thoughtful reasoned treatment of the evidence.

And so, for example, Read does not offer reasoned refutation of Murray’s account of Pushmataha and Jackson, although such refutation is possible. Quite the contrary, Read does not do anything to invite a reasoned evaluation of the evidence. He merely establishes that Murray was known as “Alfalfa Bill” in hopes the audience will always associate that evidence with bucolic buffoonery and dismiss it out of hand. By the same token, Read does not take issue with Wyman’s credentials, nor does he try to refute Wyman’s accounts of the Choctaw traditions surrounding Jackson and “OK.” He tries to establish the feeling instead that sophisticated readers understand that Wyman’s ben trovata comment indicates he was merely indulging in a little tongue-in-cheek academic gag.

Read concludes his discussion of the Choctaw etymology with the statement that the evidence he has surveyed is the product of emotional Indian lovers and that “the weight of the evidence is conclusively against” the Choctaw etymology. (17) This is a startling conclusion indeed, since he has presented no evidence to refute, conclusively or not, the evidence for “okeh.” Even if one totally accepts Read’s objections – Murray was a buffoon; the term was promoted by Indian lovers; Wyman was a practical jokester, the Pushmataha-at-New-Orleans anecdote is too good to be true – none of these factors invalidate the Choctaw etymology. Indeed, they are all part and parcel of that etymology. They all speak for its widespread popularity and usage of the expression in vernacular speech. Misunderstanding, embellishment, fraud and chicanery are often crucial factors in the origin, meaning, usage and popularity of words, especially vernacular colloquialisms such as “okay.” Indeed, the etymology that Read champions later in these papers is one that he deems particularly valid because it was “engineered” through a clandestine conspiracy.

The only evidence Read presented in the “Folklore” paper documented the depth and breadth and scope of the popularity of the Choctaw etymology which achieved the near-mythic status in folklore. Read spends considerable effort in these papers documenting on one hand the popular, widespread association of “OK” with Jackson and then arguing on the other hand against the relevance of that evidence in explaining the popularity of the expression. Indeed, he probably spends more time in the papers discussed here arguing that point than on any other single topic.

It seems that with this paper Read established a fundamental principle on which on which the discussion of “OK” or “okay” would be based, and that inviolable principle was that uncultured, non-Anglo-Saxon, “popular” material had no place in the discussion. According to Read, what may appear to be sound historical evidence is really nothing more than vindication of his premise that the material is really the “cleverest and most seductive” of all of the the bogus etymologies.

READ’S “FIRST STAGE” PAPER

In another paper, “The First Stage in the History of ‘O.K.'” Read offered early instances of “O.K.” appearing in newspapers beginning with a March 23, 1839 issue of a Boston paper. He offers a lengthy explanation and examples of a fad that emerged in Boston about 1838-9 which delighted in “sportive” use of language, spelling and abbreviations such as “N.C.” for “’nuff ced” or “K.Y.” for “know yuse.” This fad was documented by numerous examples of “O.K.,” “sportive” and otherwise, collected by Albert Matthews of that city.

He also described how the speech of the frontier, in particular the “transmontain” region between the Allegheny and Rocky Mountains, was in vogue at the time and was the source of many linguistic innovations. He offers several examples of this as raw material for “sportive” use of the language.

The dozen early instances of the use of “OK” cited in the paper are colloquialisms expressing affirmation. In five of the twelve instances, the expression is not glossed. The reader is assumed to be already familiar with the term and its meaning. In the remaining instances, the expression is glossed as “all correct,” although in some instances “all correct” does not seem to be a particularly good fit semantically or syntactically. In all instances the term is used in an informal, uncultured context. Indeed, in one instance an apology was later made for using the term at all. In none of the dozen quotes offered by Read is the expression used as an abbreviation for anything.

Read closes the paper with this startling summation:

|

…in the spring of 1839, O.K. became current as standing for “oll korrect,” in a slang application of all correct, and from there it became widespread over the country. Thus the emergence of O.K. is well accounted for. (“First Stage,” 27)

|

This conclusion is startling because, except for one instance in which he speaks about the use of humor in “the emergence of ‘oll korrect,'” that term does not appear any place in the paper until this summary. He offers extensive documentation of other sportive abbreviations (over 125 citations), as well as extensive background and interpretation on how one should expect to see “O.K.” glossed. He offers examples of “O.W.” glossed as “all right” beginning some nine months before the first occurrence of “O.K.” He offers an instance of “a.r.” glossed as “all right” before the first occurrence of “O.K.” But he offers not one instance of the appearance of “oll korrect” in the public record during this time.

This includes every instance in which the style of writing might conceivably be considered “sportive.” This includes instances in which the writer spells “Boston” as “Bosting” or uses N.S.M.J. for “‘nough said ‘moung gentlemen” or uses the phrase “Vell, vot ov it!” but still glosses “O.K.” as “all correct.” That seems to be fairly persuasive evidence that the “sportive” expression “oll korrect” has not yet been coined. Moreover, most of the instances of “O.K.” cited by Read occurred in settings which did not by any stretch of the imagination use “sportive” phraseology or spelling.Regardless of the conclusion with which he ends this paper, the evidence he presents argues very exhaustively and unambiguously that “OK” was widely used at this time as a popular colloquialism expressing affirmation but not as an abbreviation for “Oll Korrect.”

READ’S “SECOND STAGE” PAPER

In his next paper “The Second Stage in the History of ‘O.K.,'” Read continually refers to the general usage or general circulation of “OK” as “Oll Korrect,” but he is able to offer only two examples of clear cut instances of this “general usage.” He offers several citations of a story that Jackson used “OK” for “Ole Korrect” or “Oll Korrect” and notes that this material was very popular and widely circulated. However, he maintains the policy he established in the “First Stage” paper of dismissing as irrelevant any evidence that associated Jackson with “OK.” He also dismisses evidence associating William Henry Harrison with “Oll Korrect,” saying it is a case of “simply a transference from one false story to another.” -“Second Stage,” 89-91

He offers two examples of “OK” being glossed as “Oll Korrect” in jest as part of a list of similar outrageous inventions (“Second Stage,” 97, 99) But out of the some 80 uses of “OK” he cites in the paper, excluding those he “disposes of” because they associate “OK” with Andrew Jackson or the frontier, Read is able to find only two instances in which “OK” is employed in general usage or general circulation as “Oll Korrect.” Neither originated in either Boston, where Read claims the phrase was created and promoted, or New York. Both are from Ohio (which was not far removed from “frontier” at the time.). One occurred in April of 1840, and the other in September of the same year, well after the stories associating it with Jackson had become popular.

The evidence he presents in the “Second Stage” paper documents extremely persuasively that “OK” was very widely used during this time as a colloquial expression of affirmation, but it was not employed in general usage as an abbreviation for “oll korrect” (except in connection with Jackson) any more than it was in dozens of other ways.

The “Second Stage” paper, however, is not primarily about the “Oll Korrect” etymology, but rather about the “Old Kinderhook” etymology. This use of “OK” was first noted by Read in the March 23, 1840 issue of The New York New Era, a paper affiliated with the democratic political party. The paper carried a notice regarding a meeting of the a group of Tammany Society “O.K. Boys.”

|

The Democratic O.K. Club, are hereby ordered to meet at the House of Jacob Colvin, 245 Grand Street, on Tuesday evening, 24 the inst. at 7 o’clock.

Punctual attendance is requested.

By order,

William Stokely, President

John H. Low, Secretary

(“Second Stage,” 84) |

Read might give the impression the Tammany groups were merely a New York political group named after a building, Tammany Hall – also popularly known as the Great Wigwam – but that is not the case. The Tammany groups or social clubs as well as the buildings were named after the individual described as “the greatest and best chief known to Delaware tribal tradition.” (Mooney, “Tammany,” 683) There were Tammany Societies up and down the young country, and they had been instrumental in the formation, development and survival of that republic. Tammany is sometimes referred to as the patron saint of America. (See the chapter “America’s Patron Saint” in Jack Weatherford’s Native Roots: How the Indians Enriched America.)

Because the Tammany Society is so central to Read’s “old Kinderhook” etymology, the subject warrants some discussion:

|

…it appears that the Philadelphia society, which was probably the first bearing the name, and is claimed as the original of the Red Men secret order, was organized May 1, 1772, under the title of Sons of King Tammany, with strongly Loyalist tendency. It is probable that the “Saint Tammany” society was a later organization of Revolutionary sympathizers opposed to the kingly idea. Saint Tammany parish, La., preserves the memory. The practice of organizing American political and military societies on an Indian basis dates back to the French and Indian war, and was especially in favor among the soldiers of the Revolutionary army, most of whom were frontiersmen more or less familiar with Indian life and custom. . .. . .The famous Tammany Society. . .was founded in 1786 by William Mooney, a Revolutionary veteran and former leader of the “Sons of Liberty,” and regularly organized with a constitution in 1789 (most of the Original members being Revolutionary soldiers), for the purpose of guarding “the independence, the popular liberty, and the federal union of the country,” in opposition to the efforts of the aristocratic element, as represented by Hamilton and the Federalists. . .

The society occasionally at first known as the Columbian Order took an Indian title and formulated for itself a ritual based upon supposedly Indian custom. Thus, the name chosen was that of the traditional Delaware chief; the meeting place was called the “wigwam”; there were 13 “tribes” or branches corresponding to the 13 original states, the New York parent organization being the “Eagle Tribe,” New Hampshire the “Otter Tribe,” Delaware the “Tiger Tribe,” whence the famous “Tammany tiger,” etc. The principal officer of each tribe was styled the “sachem,” and the head of the whole organization was designated the kitchi okeemaw, or grand sachem, which office was held by Mooney himself for more than 20 years. Subordinate officers also were designated by other Indian titles, records were kept according to the Indian system by moons and seasons, and at the regular meetings the members attended in semi-Indian costume. . .

For the first 30 years of its existence, until the close of the War of 1812, nearly the whole effort of the society was directed to securing an foundations of the young republic and it is possible that without Tammany’s constant vigilance the National Government could not have survived the open and secret attacks of powerful foes both within and without. – Mooney, “Tammany”

|

In 1812 a branch of the Tammany Society was formed at Hamilton, Ohio. They called their meeting place “Wigwam No 9,” and met to listen to “long talks.” (“Tammany Society”) Details of Choctaw culture were very popular and well known at that time and “long talks” or “great talks” were common popular translations for Indian (Choctaw and others) expressions for a speech. The Tammany faithful delighted in using what they perceived as Indian expressions whenever possible as the quote above suggests and as this newspaper notice illustrates:

|

NOTICE.–The members of the Tammany Society No. 9 will meet at their wigwam at the house of brother William MURRAY, in Hamilton, on Thursday, the first of the month of heats, precisely at the going down of the sun. Punctual attendance is requested.”By order of the Great Sachem. “

The ninth of the month of flowers, year of discovery 323. William C. KEEN, Secretary – “Tammany Society“

|

Read might also give the impression that the Tammanies were sophisticated and effective molders of public. This perception is greatly at odds with the more widespread perception among the civilized, cultured elements of society that the Tammanies were little more than mobs of uncouth hell-raisers. This was certainly the perception about the Ohio group:

|

They exerted an influence which was extensively felt, and in the short period of their existence did considerable mischief. (Mooney, “Tammany Society”)

|

The New York Tammanies of 1839-40 were not very different, nor were they perceived as very different, from the Ohio Tammanies of 1812. The microfilm copies of The New York New Era from July 19 to the end of that year offer about the only accessible record of the day-to-day offerings of that New York City democratic publication at the time preceding the “OK boys” notice in March of ’40. (New York Democratic-Republican New Era)

Some things are evident from this six month long “snapshot” of the Tammanies. The most obvious thing is that they were not serious, sophisticated users of the press, nor were they sophisticated social or political activists. Their interest instead seemed to be limited to taking every opportunity to use what they perceived to be Indian expressions and performing what they perceived to be Indian rituals and practices. While the six months of the New Era on microfilm documents in great detail the meetings, agendas, motions, debates and so forth of other democratic groups around the city, there was nothing like this concerning the Tammanies, with a couple of minor exceptions. Press reports about the Tammanies were almost entirely limited to notices about meetings nearly identical to the ones in the Ohio papers decades before, notices that delighted in using what the Tammanies perceived to be Indian expressions. Here’s an example.

|

TAMMANY SOCIETY OR COLUMBIAN ORDER Brothers – A regular meeting of the Institution will be held in the Council Chamber of the Great Wigwam, on MONDAY EVENING, Dec. 2d, at half-an-hour after the setting of the Sun.

General and punctual attendance is particularly desired.

By order of the Grand Sachem,

JOHN M. LESTER, Secretary

Manhattan, Season of Hunting, Eleventh Moon, Year of Discovery 48, of Independence 65th, of the Institution 51st.

N.B. An election of Sachems will take place on the above evening. |

Many, perhaps most, of these notices included a note similar to the one in this notice that the upcoming meeting would feature some ritual associated with the election or installation of sachems. If there was much purpose to the Tammany meetings as anything more than an occasion to delight in Indian speech and practices, it is not apparent in the Tammany papers of the time.

A parade organized by the democratic “Butt Enders” in November of 1839 is also insightful. The democratic New Era noted that it included a contingent of Bucktails Boys mounted on white horses and featured a large painting of an Indian purporting to be “Old Tammany.” The Bucktails were so named because instead of wearing the usual items of Indian regalia favored by Tammanies, they wore buck tails on their hats instead plumes, to commemorate the totem of Chief Tammany, the deer.

The New Era devoted a column to the parade. The rival Whig paper The New York Herald, on the other hand, devoted a column and a large engraving to the event in the next issue and another column and large engraving a few days later. The article describes how the Tammanies had traditionally been identified by Indian names such as Mohawk (as the Mohawks who performed the Boston Tea Party, for example), or as the Bucktails until the summer of 1830 when the efforts of various factions to assume power within the Bucktails or Tammanies began engendering a myriad of splinter groups with rough-and-tumble, but not necessarily Indian, names. (“Humors“)

These Tammany groups were not only very uncouth, they were also very successful. It was the success of this popular, rowdy, frontier approach to politics that had decided previous elections, and the Harrison partisans decided to exploit (or manufacture) a frontier, rough-and-tumble image for their candidate.

As a result, Harrison became popularly known as Tippecanoe, after the famous Indian War battle. So popular was this Indian-derived designation that Harrison’s most popular slogan, “Tippecanoe and Tyler, Too” used it in place of his name. Supporters of Harrison began developing Tippecanoe clubs in response to the success of the Tammany groups, and Read documents that the Tippecanoes sometimes referred to their activities as “pow-wows” (“Second Stage,” 95) just as the Tammanies sometimes did theirs (90).

In general, the Whig efforts to sell a rough-and-tumble, log-cabin-and-hard-cider image of Harrison were definitely less successful than the various rough-and-tumble images with which the Tammanies sold their democratic candidates. The Tammanies often characterized Harrison as the “granny” general, or “petticoat” general, and these jabs seem be well received by the public. Sometimes the imagery of the conflict between the Tammanies and the Tippecanoes was fairly explicit, as in this description of the Tammanies by the pro-Harrison New York Morning Herald .

|

In the streets, a few miserable squads of these squalid creatures, who, in the wantonness of barbarism, call themselves “huge paws,” “roarers,” “buttenders,” and the like, were crawling along to a fife and drum, that made the very horses in the omnibuses stop, fling up their tails, and burst forth in a broad “ha! ha!” Tammany Hall, up to near ten o’clock, was deserted, and waiting for the tribes; but it seems that as great panic has seized these miserable barbarians as did the savages on the Tippecanoe river, where General Harrison approached their settlement to chastise their insolence. (New York Morning Herald, April 11, 1840, p.2, col. 1)

|

Perhaps a moment should be taken to note the general tone of the piece. It is a free-and-easy, tongue-in-cheek swipe at the Tammanies. It is not intended to be taken too seriously or too literally. As an example of the tone of the campaign, it is very enlightening. As an example of journalism, it is not outstanding, to say the least. And it is not, nor does it have any pretensions of being, an example of sound historiography. To suggest that a sentence or a couple of words can be taken from this story to serve as the factual basis of some cultural phenomenon is highly problematical at best.

The 1840 newspaper notice about the some of the Tammanies meeting as the “OK Boys” was documenting a rather ordinary phenomenon as these groups constantly evolved and reorganized. In this case, a group of Tammany Bucktails or Tammany Old Butt-Enders began calling themselves the OK Boys.

One newspaper account stated that The O.K. Club was “said to number 1,000 bravos…”. – Second Stage, p. 89 Bravos was the shortened version of the more common “Indios Bravos,” or “Wild Indians.” “Bravos” was often used by itself in English to mean “savage.” Other accounts more or less characterized the O.K. Boys as the standard bearers of the Tammanies. – Second Stage, 94; Second Stage 95

The vulgar, improper nature of these groups was expressed in their catchwords or war cries, and this particularly applied to “OK.” It was widely noted that there was something special and inexplicable about this use of “OK” from its very earliest days.

Indeed, four days after the initial newspaper notice by the OK boys another notice appeared in the same paper with the headline, “Meeting To Night,” followed by the large letters “O.K.” That notice the expression “O.K.” proved to be a thinly veiled suggestion to the OK Boys to break up a meeting by the political rival party, the Whigs. The papers the next day commented how central the expression “O.K.” was to the ensuing melee:

|

About 500 stout strapping men, many of them with sticks, . . . marched three and three, noiselessly and orderly. The word, O.K, was passed from mouth to mouth, a cheer was given, and they rushed into the Hall and up the stairs, like a torrent. (85)

|

Another paper described “shouting the watchword of the New Era, ‘OK.'” Another paper called “O.K” the “war cry” (italics in the original). (85)

In the coming months “OK” was described as cabalistic on many occasions. The term “cabalistic” was used in a virtual sense in that the expression seemed to have an inexplicably popular and inexplicably expressive dimension to it.Read also described the term as cabalistic, but argued that it was cabalistic in the literal sense of deriving some special significance through secret ritual, secret password or secret society. He argues passionately for a theory that the publisher of the New Era organized and engineered a clandestine conspiracy to promote a special, secret use of the expression “O.K.”

Read put forth this theory because some months after its initial story about the OK Boys, the New Era carried the ad for the “O.K.” lapel pin mentioned earlier commemorating the “hero of New Orleans,” Andrew Jackson. The notice described “the very frightful letters O.K., significant of the birthplace of Martin Van Buren, old Kinderhook, as also the rallying word of the Democracy of the late election, ‘all correct.'” The story went on to note that the pin could be purchased at Mr. P. L. Fierty’s, 486 Pearl Street, and ended with an optimistic hurrah that the upcoming elections would turn out “O.K.” – “Second Stage,” 86

On the face of it, this notice seems to be a rather unremarkable advertisement in a very unremarkable publication. Catalogs such as the OCLC Union List of serials often include the description that the New Era was “largely advertisements,” and that is very true. It was only published for about four years and never rose much above the level of a modern day “shopper” except that it contained daily long harangues against the formation of a national bank and promoting New York democratic politics. It was usually entirely ads except for the second page which contained the political material. One could hardly find, in the New Era, a less likely instrument of social engineering, just as one could hardly find, in the Tammanies, a group more devoid of aspirations or abilities to advance social or cultural innovations.

The “hero of New Orleans” commemorative pen was typical of the standard New Era advertisement that starts out as a humorous anecdote or human interest story and then ends up in the last sentence or two noting where the object of the story – the patent medicine or corset stays – could be purchased. It was a common practice of the day to try to disguise ads as legitimate news articles. An ad for “rheumatism plasters” that was run dozens of times in the New Era was given a “New Era” byline in an effort to make it look like a news story. Likewise, an ad for a hat store was given a “twist” to try to make it look like a democratic political notice. There is no reason to believe the OK lapel pin ad is anything other than another one of these ads.

Read perceives the notice differently. He argues in this “Second Stage” paper and then more passionately in his last paper of the series that this notice was “an important breakthrough” in the use of “OK.” He theorizes that the editor of the New Era, after months of secretly engineering the popularity of the expression “OK” through secret meetings as a cabalistic abbreviation for “Old Kinderhook” finally, in the “hero of New Orleans” lapel pin notice, announced to the public the secret, heretofore inexplicable, cabalistic meaning of the expression.

Others have not always share Read’s interpretation of the notice. The notice does not materially seem to be particularly about “Old Kinderhook.” On the contrary, it is hard to imagine a more explicit argument that in 1840 the expression “OK” was popularly associated with Jackson and the Choctaws at the Battle of New Orleans. At least the writer of the ad saw no need to explain the connection. Both “Old Kinderhook” and “all correct” seem rather to be afterthoughts to exploit the sportive acronym fad.

Andrew Jackson and New Orleans were an extremely important part of popular culture at the time. Entertainment offerings of the day included a speech at the New York Lyceum recalling the Battle of New Orleans and the exploits of “the old Hero” of that battle. (“New York Lyceum“) A fundraiser for the Tammany Temple was a ball commemorating Battle of New Orleans. (“EIGHTH WARD TAMMANY TEMPLE ASSOCIATION“) One New York establishment advertised in the New York Herald was the New Orleans Literary Depot. (“NEW ORLEANS LITERARY DEPOT“)

Moreover, the lapel pin notice did not at the time constitute an important breakthrough in the use of “OK.” “OK” for “Old Kinderhook” was not used at all before the lapel pin notice and, according to Read’s own evidence, it was not widely used after that notice. Read cites only one instance in November of 1840 of the use of “OK” used as “Old Kinderhook.” – 98

Read’s evidence, or lack of it, is compatible with that of other historians in that Van Buren’s birthplace, Kinderhook, is sometimes associated with the man in political and campaign usage, but he was not by any means known as “Old Kinderhook” in general usage. Read elsewhere expresses consternation that a “sound historian” knowledgeable of the events surrounding “Old Kinderhook” should be “so remarkably vague” to the Library of Congress about the etymology of “OK.” In fact, this historian’s explanation of the rise of “OK” was not vague at all; it just didn’t include in any way “Old Kinderhook” but rather associated the expression with Andrew Jackson. – “Folklore,” 13

Even the one example Read cites of general usage of the name “Old Kinderhook” may have been more tongue-in-cheek than an example of “general usage.” This usage occurs in a notice about a rally for Van Buren and another Tammany candidate, Richard Mentor Johnson. “O.K.” and “Old Kinderhook” references to Van Buren were used to maintain parallelism with the use of “O.K.” and “Old Kentuck” to refer to Johnson. “Old Kentuck” was in wide circulation at the time, as documented by Read. (“Second Stage,” 86) But it was the nickname for an important national Whig leader of the day, Henry Clay. For the Democrats to suggest that the popular nickname “Old Kentuck” referred to the Democratic Johnson was a gag to take a slap at Clay and the Whigs.

Referring to Richard M. Johnson as “The Hero of the Thames” was also a slap at Harrison who usually accorded that distinction, and was celebrated in that way in a song “The Hero of the Thames” promoted for months in the New York Morning Herald. In fact, the description “Hero of the Thames” fit Johnson at least as much as Harrison in that it was Johnson and his troops who engaged in the crucial battle on the field. Indeed, according to the widely circulated anecdote, Johnson was the individual who killed Tecumseh after being wounded by the Shawnee chief. Harrison, on the other hand, was the butt of Tammany efforts to ridicule the extent of his heroism in battle and, indeed, his very manhood, on occasion portraying him in a dress. This raises the question about the extent to which, if any, the use of “Old Kinderhook” in this instance was much more than one more facetious element of the gag. To take sportive acronyms in this newspaper story literally is to miss the whole point. And yet Read takes the story very seriously and very literally, arguing not only that it documented a general usage, but the general usage from that time forward.

Finally, it should be noted that according to Read’s own policy, the entire lapel pin notice should be dismissed out of hand, associating, as it does, the expression “OK” with Jackson. The whole purpose of the notice is to promote the sale of the pin designed to commemorate Jackson at the Battle of New Orleans. This particular instance, however, Read does not characterize the material as “folklore” or “fabrication” as he does other material dealing with “OK” and Jackson. In this case, says Read, “a particular individual, the Tammany editor, simply set down the truth as he knew it.” (note, 89) Read says his discovery of the notice was the “important breakthrough” in the etymology of “O.K.” “With that piece of information, the whole picture appeared to fall into place.” – “Successive Revisions,” 251- 252

It is characteristic of Read’s interpretation that he would maintain that a substantial body of material associating “OK” with Jackson – material by reputable historians that was widely accepted and widely circulated not only at that time but to this day – did not have any bearing on the popularity of the term, but that two words take out of context from an obscure notice about an “OK” lapel pin commemorating Jackson – a notice that apparently went unnoticed until Read’s promotion of it a century later – would be, according to Read, the seminal event in the popularity of the expression.

By the same token, it is characteristic of Read’s interpretation that he would maintain that a large body of popular and widely accepted material dealing with Jackson is irrelevant because it was “invented,” but that the seemingly obscure and inconsequential citation he discovered “looms overwhelmingly important” because it was clandestinely “engineered.”

Read ends the “Second Stage” paper with a reaffirmation of the importance of his discovery dealing with “OK.” Out of the 80 or so instances of “OK” he documents in this paper alone, not counting those dismissed out of hand because they associate the expression with Jackson or the frontier, one is the phrase “old Kinderhook,” and one is the sportive use of “Old Kinderhook” some five months later in an anti-Whig gag. On the basis of these two isolated instances and an enormous amount of interpretation – “sheer, gratuitous, armchair theorizing” according to one of his critics – “Successive Revisions,” 258 – Read concludes that:

|

…in the history of O.K. “Old Kinderhook” looms overwhelmingly important in explaining how it got fastened into the American (and World English) vocabulary. – 88, note

|

He ends the paper with the statement that he has established “the trajectory of O.K. as it rocketed across the American linguistic sky.” (102)

Read took this line of interpretation to the point that he considered the lapel pin notice the “origin” of “O.K.” All previous examples of OK he came to regard as incipient forms of the “Old Kinderhook” etymology. Although the expression seemed to be used by those with no ties to Van Buren about as much as it was by the Tammanies, Read argued that those uses were really attempts by opponents of the Tammanies to de-value the term. Read speculated about what it would take “to modify the picture” to the extent the “‘Old Kinderhook’ origin” would cease to be regarded as the only true one. Read’s friend, H.L. Mencken wrote in an article for New Yorker that many “have busied themselves with trying to find examples of O.K. before March 23, 1840. . .but always without success.” (259-260)

When Heflin, the Dicionary of American English staffer in charge of the OK entry, pointed out the obvious, that “the expression O.K. was widely known in 1839 and 1840” Read’s response was “No one can deny this or does deny this.” (262)

There are a couple of other problems with the sportive “oll korrect” and cabalistic “Old Kinderhook” etymology.

First, “OK” has always had some widely understood and accepted special connotations of impropriety to it. The reference to the “frightful letters O.K.” in the Jackson lapel pin ad has already been noted.

Early in 1840 a theatrical weekly used “O.K.” in a story about a benefit for the widow and children of a popular entertainer: “The net proceeds was upward of $1,200, O.K.” – “First Stage,” 18 – “O.K.” appeared about three weeks later in the same paper, and Read says the editor apologized the next day for using the expression because it was not appropriate for inclusion in the paper. (18-19) This paper had no problem with sportive or colloquial phraseology in general, and there was certainly nothing improper about the benefit-for-the-widow-and-children story. However, there was definitely some widely appreciated dimension to the expression “OK” that made it unacceptable in ways similar colloquialisms were not.

One news story referred to the “mysterious letters, the power of which, when exerted, is so fatal to the peace and harmony of the city…” – Second Stage, 91. A short fictional newspaper piece said “Drums beat in the street and shouts of O! K! made the night hideous.” (99) Brinton’s implication that Choctaw was the language of “ignorance and immorality” while English was the language of “godliness and civilization” comes to mind.

Even today the use of the expression is not considered standard English, as any grammar or high school student who used it in an essay or paper has probably learned.

The second problem with the “oll korrect” or “Old Kinderhook” etymologies is semantics. This is obviously the case with “Old Kinderhook.” No one would seriously argue that in any but one or two instances the expression “OK” has been used to express “Old Kinderhook.”

But even “Oll Korrect” is often not a good semantic fit for the expression “OK.” This is a very characteristic and widely acknowledged aspect of many, if not most, of the early uses of “OK” documented by Read. In these instances when “OK” as “all correct” does not quite seem to fit, the traditional, non-abbreviation “okay” seems to fit perfectly. So does the Choctaw “okeh” meaning “it is so and not otherwise” discussed earlier. The linguist’s observation that “the occurrence of okeh in Choctaw conversations in much the same syntactic and semantic environments as the American OK” is remarkably pertinent.

And so, for example, charitable net proceeds of upwards of $1,200 would not be characterized as “all correct.” But it would be perfectly natural to pronounce them “okay” or “okeh.” By the same token, failure to hold a meeting might be “okay” or “okeh,” but it would not be “all correct.” (“First Stage,” 13) The attendance at a concert (“the house” in theatrical parlance) might be “okay,” but it would not be “all korrect.” (“Successive Revisions,” 265) Even when those instances of “OK” are glossed as “all correct” the gloss is reasonable because “all correct” conveys the general idea about as accurately as anything else might. But in almost all of those cases, the essential “feel” of the word is not conveyed by “all correct.” To use the terminology of the Choctaw linguist, the “syntactic and semantic environments” do not quite fit. In all of those cases, the tradition “feel” of “okay” is a much better fit.

Heflin cited “O.K.” used in reference to a mint julep and a bargain and pointed out that thinking of those things in terms of “OK” is perfectly natural, but in terms of “all correct” is problematical. Read acknowledged the point but minimized its significance. – 13-14

It should probably be noted for the record that Read published a “Later Stages in the History of ‘O.K.'” after the “Second Stage” paper, and in that later paper he reviewed his conclusion of the previous “Second Stage” paper, that the general usage of “OK” was a product of “Old Kinderhook”:

|

The Tammany leaders, drawing upon the symbolizing of “Old Kinderhook,” intended their slogan to mystify the public, but the concentrated attention of the Whigs wrested the expression from them and assured its place in general usage.” – Later Stages, 83

|

In this paper he cites and disparages several instances in which “the erroneous Choctaw etymology” is explicitly used: Woodrow Wilson’s use of “okeh,” a sampling of three instances of “oke” used in England, a play on words in which “okeh” becomes “okie” as in “okie-dokie” as well as the nickname for an Oklahoma resident in a popular song proclaiming “I’m a Pale Face Okie…From back in Muskogee.” – 95-96

Read also published a paper devoted exclusively to discussing whether or not Andrew Jackson could spell.

His last paper in the series was titled (with what was apparently unintentional irony) “Successive Revisions in the Explanations of ‘O.K.'”

READ’S “SUCCESSIVE REVISIONS IN THE EXPLANATIONS OF ‘O.K.” PAPER

In this last paper of the series Read deals with a subject he has for the most part ignored in earlier papers, even though it is by consensus the earliest known example of “ok” being set down on paper. It is the quintessential “We arrived OK” notation in the hand-written diary of a traveler going from Boston to New Orleans in 1815. The traveler’s name was Richardson, and the “Richardson OK” occurs in the entry for February 21, 1815. It is, of course a hand-written account with many strike-outs and insertions, but by most reckonings that entry includes this sentence “Arrived at Princeton, a handsome little village, 15 miles from N Brunswick, ok & at Trenton, where we dined at 1 P.M.” (“Successive Revisions,” 246)

This “OK” was written by a traveler to New Orleans who presumably was interested in events in that city and in touch with someone who lived there, and it was used at a time when that city (and the nation, for that matter) was still abuzz over the Battle of New Orleans. It is perfectly plausible, but perfectly speculative, that the traveler had learned of the expression “OK” from the New Orleans friend or family member and then used that expression in his diary. It is possible Richardson read the expression in press accounts of the events surrounding the battle because such accounts were common and popular, although those accounts seldom included much or any information about Native contributions to the victory, and no usage of the Choctaw in the public record has yet come to light.

Woodford Heflin summarized how this occurrence of “OK” was regarded in many quarters, coming as it did some twenty-five years earlier than the flurry of occurrences of “OK” coming in 1839-40:

|

Some people may argue that the very fact of its earliness casts doubt upon its genuiness. This fact, of course, should make one pause in making a hasty conclusion, but in itself the argument is negative and is not necessarily true. Colloquial language very often does not get written down until long after it has come into common use. (95)

|

Heflin, always the meticulous researcher, invested substantial “unhasty” thought and research on the question, even consulting a handwriting expert. “In my opinion,” he wrote, ” it is a genuine usage.” (94)

There was certainly room for different opinions regarding this notation, and the “Successive Revisions” paper is ostensibly about how the DAE editors grappled with how to treat the notation. In fact, however, the paper is overewhelmingly the notice Read served about what would happen to anyone from “a mere snip of a secretary” to the chief editor (and in particular at Woodford Heflin) who did not take his “Old Kinderhook” etymology sufficiently seriously.

A DIGRESSION ON FRONTIER GEOGRAPHY

Before leaving the subject, mention must be made of an significant “frontier” dimension to the expression “OK,” and that is its recurrence as a place name. The first examples that come to mind are probably the “OK Corral” of gunfight fame and the “OK Mine” of Central City, Colorado, which was also home, incidentally, to the Marx Brothers’ OK Clothing Store. It is hard to believe these things were named ‘OK’ to commemorate a New York City politician. But the most interesting and provocative “OK” was and is – where else? – Okay, OK.One current web site about ghost towns says that:

|

Okay was a frontier town that grew and prospered in the pre civil war times. In 1871, the railroad came through and the town moved to its present position. There is not much remaining of the original town. ( Okay)

|

This description is not exactly wrong. It is certainly more right than the widely circulated assertion that town of Okay was named for the Okay Truck Company. The town was officially given the name Okay in 1919; the OK Truck named in 1923. – McMahan, 13, 27

Both the “ghost town” and the “truck company” assertions imply the situation was much more well defined and straightforward than is the case.The Three Rivers area of what is now Oklahoma figured very prominently in frontier history. The first trading post was established in 1806 but was destroyed in its first year by Pushmataha because it was dealing with Osages, the enemies of the Choctaws. Other traders followed, until trading posts and more than 30 log cabins appeared in a two or three mile stretch of the Verdigris River. One of Astor’s prime competitors, Auguste Chouteau, established not only a trading post there, but a facility to build keel boats to ply the rivers. Chouteau’s facilities was later converted to an Indian Agency as the federal government became involved in the administration of Indian policies. – 6-8

This relocation of the Chouteau facilities was only one example of a common and recurrent incident in the history of the area. Flood or fire or war would often cause a small settlement or trading post to be relocated a few hundred yards up or down the river. When the railroads came through, the centers of the community tended to gravitate toward the area that offered the most effective access to the railroad.

Moreover, the arrival of the railroads and later the implementation of U.S. Postal Service to the area meant that the community or the loose cluster of smaller communities acquired official names, perhaps for the first time. For example, the first railroad facility in the area was the Corretta switch and the community that gravitated around that facility became known, more or less officially, as Corretta Switch. When postal service came to the region, one of the prime challenges it faced was to adjudicate the various claims regarding which of the traditional names should be used and where the facility should be located. The post office went through a series of name changes, the most recent being in 1919 from “North Muskogee” to “Okay.”

How prominently did the name “Okay” figure in the early history of what is now the town of Okay? Did, for example, the community identify itself as “Okay” in the early 1800’s before it relocated near the railroad in 1871 as the “ghost town” quote above implies? There seems to be no hard contemporary documentation in the current literature one way or the other. There appears to have been an Okay bank before 1915. (20) It is highly unlikely that any hard evidence will come to light documenting the use of the name “Okay” that predates the published uses of “OK” beginning in 1839.

COMMENTARY AND CONCLUSIONS

The problem of the etymology of Okay, OK is the problem of “okeh” or “OK” in microcosm. The history of the region and the preponderance of other place names in the area drawn from Muskogean culture – from Pushmataha county to the town of Muskogee – suggest very strongly that “Okay” is merely a variant spelling of the Choctaw expression that Byington spelled “okeh.”

The alternate view, that the name “Okay” is a corruption of the acronym “O.K.” which stands for “Old Kinderhook” may be more complicated and dubious, but it places the discourse squarely within the civilized context of Anglo-Saxon culture and the published record which many liberally educated English language researchers tend to assume is the only valid and legitimate one. The self-evident difference between Choctaw “ignorance and immorality” on one hand and Anglo-Saxon “godliness, and civilization” on the other noted by Brinton comes to mind.

Read’s out-of-hand dismissal as “folklore” of anything that is colloquial or popular or “uncultured” is a profoundly striking example of such thinking.

The Random House Historical Dictionary of American Slang lists “okeh” as the obsolete equivalent of “okay” four times but says that “[w]ithout concrete evidence of a prior and established English borrowing from Choctaw-Chickasaw” the claim that this “okeh” – the obsolete form of “okay” – is derived from the Choctaw “okeh” is no more warranted than similar claims about the Liberian Djabo “O-ke,” the Mandingo “O ke,” or the Ulster Scots “Ough, aye!” – II, 708